The possible collapse of the Atlantic Overturning Current is no longer considered a distant climate fairy tale. New studies and safety analyses show: The danger is small, but real and its consequences would also affect Switzerland. How real is the risk of an AMOC tipping point?

For a long time, the possible collapse of the Atlantic overturning circulation, the so-called AMOC, was regarded as a theoretical extreme scenario. But this assessment is changing. New studies, security analyses and even intelligence reports now treat the AMOC as a real risk factor. This turns an abstract climate model into an issue with geopolitical and economic significance, even for countries that are not located by the sea, such as Switzerland.

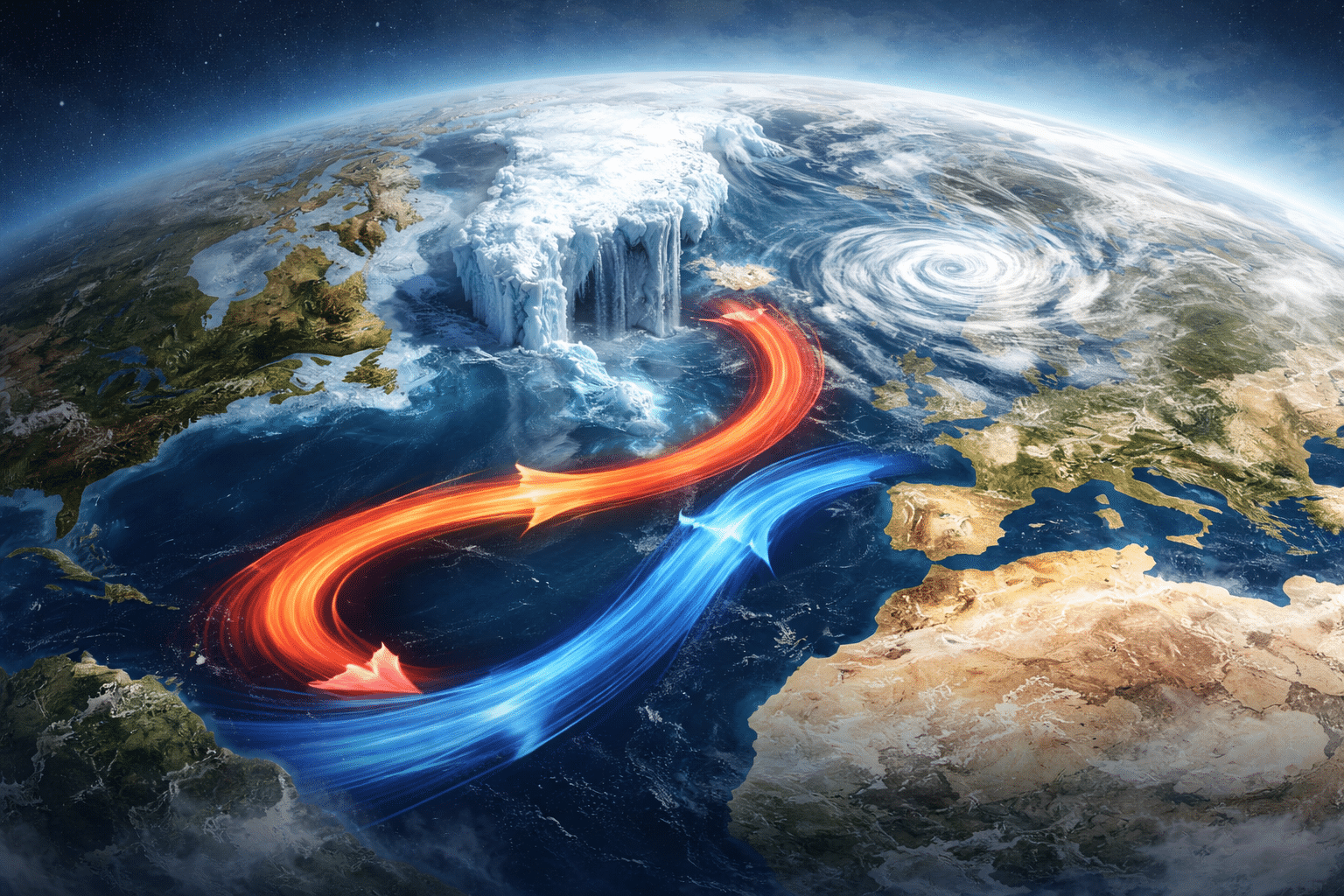

The AMOC is a huge system of ocean currents that transports warm water from the tropics to the north. In the North Atlantic, this water cools down, becomes heavier, sinks into the depths and flows back south as a cold current. This “conveyor belt” acts like a heat pump for Europe. Without it, the climate would be significantly colder, especially in northern and western Europe, but with noticeable consequences for the entire continent.

This system is stable, but sensitive. As a result of climate change, more and more freshwater from melting Greenland ice and increased precipitation is entering the North Atlantic. Fresh water is lighter than salty seawater. If the ocean is “diluted” too much, the water no longer sinks as it used to, and the motor of the current grinds to a halt. Measurements already show that the AMOC is weaker than it was centuries ago. Climate researchers such as Stefan Rahmstorf and René van Westen warn that there is a tipping point: If it is crossed, the current could collapse abruptly.

Small, but not negligible

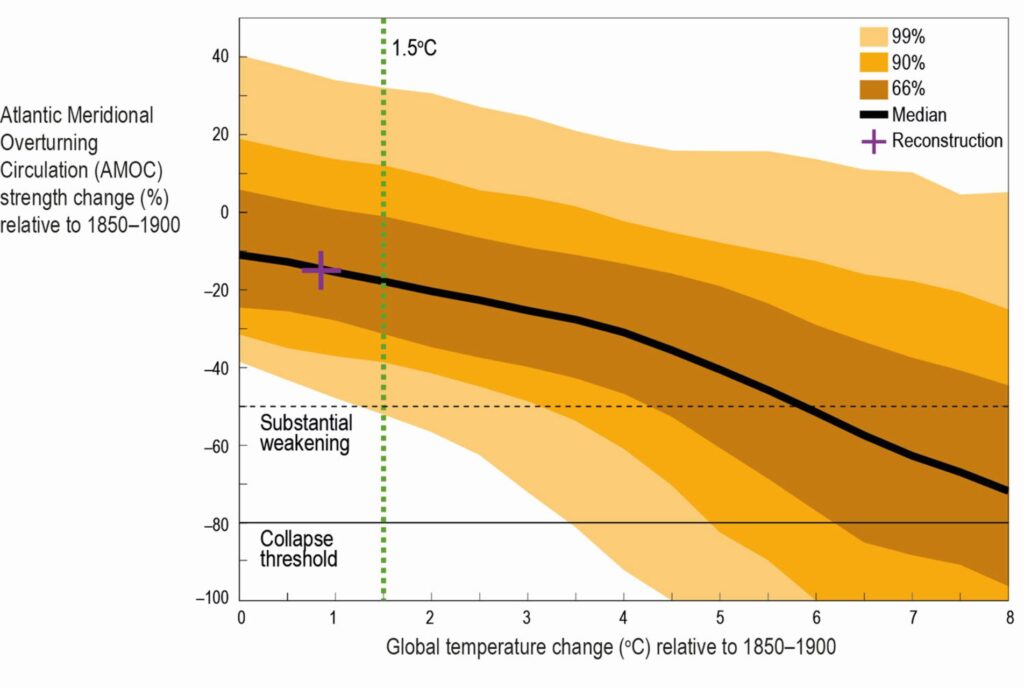

How likely is this to happen? Researchers agree that a complete collapse remains an extreme event. It is therefore not the most likely scenario in the coming decades. At the same time, it is no longer considered impossible or purely theoretical. Models show that the probability depends heavily on how high future CO₂ emissions turn out to be. If climate change continues unabated, the risk increases significantly. In scenarios with consistent climate protection, the AMOC remains weakened but stable. The chance of a collapse is therefore small to moderate, but high enough to be taken seriously.

Precisely because the consequences would be so serious, governments and security authorities are now also addressing this issue. In Germany, the AMOC was considered as a possible tipping element as part of a national climate risk analysis. The UK is investing large sums in early warning systems for climate tipping points. Iceland even classifies an instability of the AMOC as a national security threat. At European level, the European Space Agency (ESA) is planning new missions to better monitor changes in ocean circulation.

Why this also affects Switzerland

A collapse of the AMOC would massively change Europe. Average temperatures could drop by several degrees, regionally even by double digits. Winters would become much harsher, storms stronger and precipitation more extreme. Agriculture, energy supply and infrastructure would face enormous adaptation problems. At the same time, such an upheaval would have global consequences, for example for monsoon systems in Africa, India and South America.

For Switzerland, this sounds far away at first glance: no sea, no Gulf Stream, no coasts. But Switzerland is closely intertwined with the European climate and economic system. If northern Europe cools significantly, air currents and precipitation patterns over the Alps will also change. Colder, more unstable weather patterns could bring more extreme events, such as stronger winter storms, more heavy precipitation or longer cold spells. Glaciers might melt more slowly in the short term, but in the long term they would be subject to even more unstable climatic conditions. For agriculture, vegetation periods could shift, and for hydropower, runoff volumes and seasonal patterns could change. Switzerland would also be affected economically if important trading partners in Europe struggle with energy shortages, crop losses or infrastructure problems.

How do insurance companies deal with this?

The crucial question is therefore not whether the AMOC will collapse tomorrow. That is very unlikely. The real question is how much risk society is prepared to take. An event with a low to medium probability but extreme consequences is highly relevant from the perspective of insurance companies, security authorities and national economies. This is precisely why the AMOC is moving from the margins of the climate debate to the center of strategic considerations.

For Switzerland, this means that it is part of this system even without a coastline. Climate policy is therefore not only environmental policy, but also economic, security and precautionary policy. The more consistently global emissions are reduced, the smaller the chance that the AMOC will reach its tipping point. The probability is still limited today, but it is real enough not to be ignored.

Binci Heeb

Read also: The invisible cloud: why contrails are more harmful to the climate than we think